For the latest on COVID-19 (Coronavirus) click here

California’s Most Remote Destinations

California has the largest population of any U.S. state, so you might think there’s no place left that hasn’t been posted and Instagrammed. But wait: The Golden State has plenty of off-the-beaten-track attractions—from wacky museums devoted to abandoned bridges to destinations so remote they can only be reached by boat. Sure, it might take a little extra effort to ferret them out, but admit it: It’s pretty cool to say, “You can’t believe where I just went…” when you return home. So welcome to the middle of nowhere—California style.

—Ann Marie Brown & Harriot Manley

Pappy & Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace

If this incongruous structure in the desert reminds you of an Old West cowboy flick, your memory serves you well. Back in 1946, when the public couldn’t get enough of Western movies, silver-screen cowboy stars Gene Autry and Roy Rogers (and other investors) saw an opportunity, and created this 1870s-era frontier town–style movie set about 30 miles north of Palm Springs, in hard-scrabble desert near Joshua Tree National Park. The site, called Pioneertown, had camera-ready façades resembling saloons, jailhouses, and stables. Inside, the buildings doubled as tourist attractions, with a bowling alley, an ice cream parlour, and motel. The site that’s now Pappy & Harriet’s was used as a “cantina” set for Westerns well into the 1950s.

“It reminded me of the first Star Wars when they walked into the bar and saw all the aliens just drinking and having fun.” — Linda Krantz, co-owner, Pappy & Harriet’s

When Western movies died, the building became a burrito joint popular with outlaw biker gangs. In 1982, Harriet and her husband, Claude “Pappy” Allen, turned the site into the more family-friendly (but still quirky) Pappy & Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace, where you could relax with a cold one, order some Tex-Mex food, and listen to the couple and their granddaughter Kristina sing. When Pappy died in 1994, Pioneertown lost its way, until two women from New York who had visited and loved the site found out it was for sale.

“When I first walked into Pappy & Harriet’s as a customer, it reminded me of the first Star Wars, when they walked into the bar and saw all the aliens just drinking and having fun,” says Linda Krantz, who bought the business with Robyn Celia in 2003. Fixed up but forever eclectic and low-key, Pioneertown still brings together a colourful mix of people. “From bikers to grandmothers to hipsters to cowboys,” notes Krantz. Pappy & Harriet’s now attracts a mix of really good musicians and performers, such as indie-pop favourites Miike Snow and the Shadow Mountain Band. For a just-about-perfect day, hike a Joshua Tree trail, then head here to dig into a bowl of signature carne asada chili (rumoured to be made with a secret blend of tequila and coffee), and dance, clap, and hoop it up while the band plays into the night.

The Lost Coast

World-renowned State Highway 1 cruises along 650 miles of the California coast from Orange County north toward the Mendocino Coast. At its northern terminus, this epic route ends where it joins U.S. 101—but the coast continues, bending west just north of Fort Bragg.

With no major roads to access this ocean-wrapped region, it is justly called the Lost Coast. But you can explore on foot. In fact, the nearly 25-mile-long Lost Coast Trail is on the bucket list of many an avid backpacker.

Walk a wild beach to discover shell mounds, marking the spot where Native Americans once shucked clams and shellfish.

Stretching between Shelter Cove to the south and the Mattole River to the north, the Lost Coast is a wild land of forests, fog, waves, and sand. On the hike, which typically takes three days one way, you’ll be wowed by sweeping views of the King Range, its peaks soaring 4,000 feet above the Pacific. Walk a wild beach to discover shell mounds, marking the spot where Native Americans once shucked clams and other bivalves. Bring binoculars to spy impressive Roosevelt elk grazing in bluff-top prairies. Another essential item to pack: a current tide table. When the tide is high, boulder-strewn beaches (and your trail) disappear beneath the waves. Time your walk right or you could face a long wait in a flooded cove. To hike the entire Lost Coast Trail, leave one car at Mattole River Beach and the other at Black Sands Beach near Shelter Cove, or make arrangements with a local shuttle service.

Not up to backpacking but want to stretch your legs? Head for the Lost Trail’s northern terminus, accessed by following Lighthouse Road west from the hamlet of Petrolia. A three mile out-and-back trail south from Mattole River Beach affords an awesome photo op: the abandoned lighthouse at Punta Gorda.

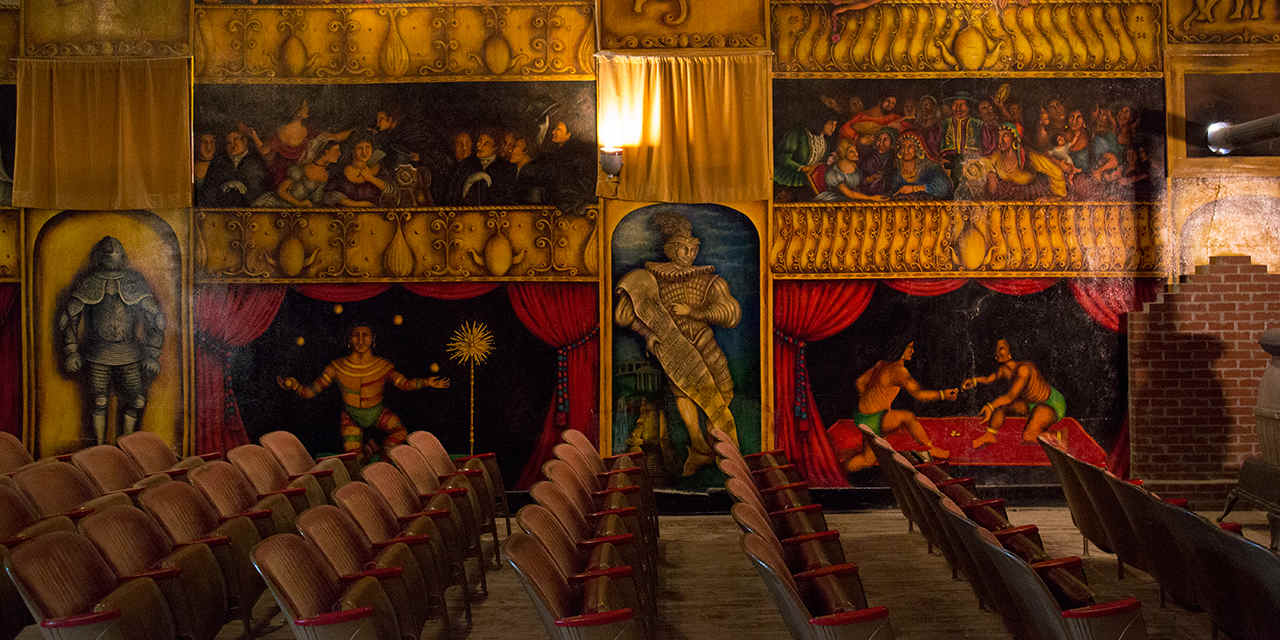

Amargosa Opera House

While some ballet dancers may dream of performing in front of adoring throngs in New York or Paris, others are drawn to settings with decidedly lower wattage. Or downright off the grid. Such is the case with Marta Becket. In 1967, the New York dancer, who had performed on Broadway and at Radio City Music Hall, dreamed of having her own place to create and perform her works.

“I went to visit this fortuneteller in New York, and she said, ‘You will be leaving New York for a very rural place, and you will be doing the best work of your life in this place,’” recounts Marta. Soon thereafter, needing a break from touring the country, she and her husband decided to go camping in Death Valley.

“The building seemed to be saying, ‘Take me. Do something with me.’” — Marta Becket, dancer and artist

While exploring abandoned adobe buildings in an area now known as Death Valley Junction, near the southeast boundary of the park, Marta came upon what appeared to be a performance space. “The building seemed to be saying, ‘Take me—do something with me.’” The next day, she and her husband did, renting the space for $45 a month. Renaming it the Amargosa Opera House, she presented her first performance there in 1968 in front of 12 adults and a smattering of kids and grandkids. “There were many performances I gave when no audience came at all,” she recalls, “but I proceeded to perform anyway.” Her solution—cover the blank walls with people. Six years later, she had finished painting her eternal audience. To stage her own works over the years, Marta created scenery, masks, and costumes, putting on productions until she was 87 years old.

One particular night, a six-year-old girl from the San Francisco Bay Area attended a show with her family. Inspired by Marta’s performance, the girl grew up to be Jenna McClintock, a former prima ballerina with the Oakland Ballet and other renowned companies. But something drew Jenna back to the desert, just like Marta was drawn years before. “It’s very strange—I really felt like I was coming home,” says Jenna, who now carries on Marta’s legacy, dancing her works at the Amargosa Opera House every weekend between November and May. (You can also take a tour to see the building and Marta’s painted walls and ceilings.) “It’s very important to preserve what Marta has done, and I also want to give it life—I want it to live on. And hopefully people will go on and make art themselves,” adds Jenna.

Can’t get enough of this quirky destination? Book a night in the adjacent hotel; some rooms are decorated with Marta’s original murals.

Bridge to Nowhere

The cart was put before the horse when road builders constructed a massive concrete bridge over the San Gabriel River in 1936. Engineers planned to build a direct route from the San Gabriel Valley to Wrightwood, but they finished this mid-point bridge near Azusa long before they built its connecting byways. In 1938, a flood washed out the partly completed road to the south, leaving the 120 foot high structure stranded. Today, the lonely Bridge to Nowhere still arcs gracefully over the San Gabriel River, providing one of Southern California’s oddest, albeit epic, hiking destinations.

Getting here requires some work. It’s a 10 mile round-trip hike on the East Fork Trail along the San Gabriel River. The trail crosses the river so often that you quickly abandon all hope of dry feet. Typically the flow is only a foot or two deep—refreshing on a warm day—but it can swell to impassable after big storms. The final stretch leads to the high-walled canyon known as the Narrows, where water squeezes through a deep and narrow gorge, spanned by the Bridge to Nowhere. Your first glimpse of the bridge is astonishing—it’s much larger and majestic than you’d expect—but the weirdness doesn’t stop here. This is also the site of Southern California’s only commercial bungee-jumping operation, run by Bungee America. You may get to see a few daredevils take the plunge. Or if your idea of fun is plunging off the side of a bridge, a bungee cord attached to catch your fall, then you could be up there too.

International Banana Museum

Home to some 20,000 banana themed items, this wacky museum could drive you ape-crazy. “Some people call it bananabilia,” says owner Fred Garbutt, who is frequently on hand to talk about his collection, housed in a bright yellow building in the sleepy desert town of Mecca, on the north end of the Salton Sea. (Just look for the guy in the banana colored sunglasses pulling up in a yellow 1960s Volkswagen bug.) “People who stop in here are always happy and surprised by what we have,” he says.

Garbutt’s collection includes banana shaped and themed gadgets and gizmos—from harmonicas and squirt guns to a “Go Bananas” slot machine and road crossing signs for banana slugs. For an a-peeling treat, have a seat on a yellow barstool and slurp a banana milkshake, nosh on banana bread, or split a banana split. Everything is deliciously weird, or weirdly delicious, depending on your perspective. Garbutt will waive your admission fee if you buy a souvenir. Surely someone back home yearns for a banana shaped fridge magnet, right?

The museum, about an hour’s drive south of Palm Springs, is usually open Friday through Monday, but call ahead before you make the trek.

Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park

Northeast of Burney lies one of the least visited state parks in California, and for a pretty obvious reason: You can only get there by boat. Ahjumawi means “where the waters come together” in the language of the region’s Pit River Native Americans, and several major watersheds convene here: Tule River, Fall River, Big Lake, Ja She Creek, and Lava Creek. The park, about 80 miles northeast of Redding, is also home to one of the country’s largest freshwater springs, all in a wild and primeval setting of aqua-hued bays and tiny, tree-topped islets.

Fortunately, you don’t need to have your own canoe or kayak to access the park. Eagle Eye’s Kayak Guide Service, based in McArthur (roughly a half hour drive south), offers kayak tours and rentals. Headwaters Adventure Company in Redding also has gear for rent (including racks for your car), and guides are available for groups of five or more—a smart idea if you’re not experienced paddlers. Outfitters can also share details on how to get to the park, where to launch, and what to pack, including binoculars for abundant wildlife. You’ll likely count more deer than people, and bald eagles and ospreys nest in the juniper trees.

If you’ve got time and love adventure, consider camping here for a night or two. There’s no need for advance reservations—chances are good you’ll have these turquoise waterways all to yourself. Rugged lava flows cover about two-thirds of the park’s 6,000 acres, all crisscrossed by a network of trails. Hike the nearly five-mile Spatter Cone Loop Trail to see volcanic features and big views of 14,179 foot Mount Shasta and 10,457 foot Lassen Peak. Along the park’s shoreline, look for prehistoric rock fish traps built by the Ahjumawi people to catch trout. Today, fly-fishing is hugely popular in the region; get details on licenses (required for ages 16 and over) and seasons from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Salvation Mountain & Slab City

Leonard Knight spent roughly three decades building this colorful mound in the Sonoran Desert as a way to share his devotion to peace, love, and a higher power. The result is Salvation Mountain: a five story high, 150 foot wide art project crowned by the words “God Is Love,” which is an exuberantly painted folk art jumble of hearts, birds, flowers, and trees. It towers over the surrounding playa and the shimmering Salton Sea, which lies roughly seven miles to the west.

Knight used hay bales, adobe clay, donated paint, plus assortment old tires, car windows, and other found objects to construct his mountain-shaped shrine. It’s a quick three minute walk on a hand-painted yellow brick road to reach Salvation’s 50 foot summit, but why rush? Take time to explore Knight’s ingenious labyrinth of crannies and caves, complete with Technicolor biblical messages decorating the walls.

Knight’s homage to God sits at the entrance to Slab City, a 640-acre plot of concrete slabs left over from a World War II Marine base. For decades, year round squatters and seasonal snowbirds have lived here rent free on state-owned land, calling it “the last free place to live in America.” There’s no power grid, no sewer, no garbage pickup, and no building codes. Knight thought Slab City was an ideal spot to construct his mountain, so he moved onto the site and spent his days building, painting, and welcoming curious visitors. In 2007, he was featured in the film Into the Wild, based on the Jon Krakauer book of the same name, which brought even more pilgrims to Salvation Mountain.

Knight died in 2014 at age 82, but his mountain remains open daily from dawn until dusk. Volunteers live at the site and maintain the structure, which is crumbling from the desert heat and sun. Admission is free, but donated cans of paint are gratefully accepted.

The Lost Sierra

You’ve heard all about the Sierra Nevada stars like Yosemite, Lake Tahoe, and Mammoth Lakes. But do you know about the Sierra Buttes? If not, you’re not alone. This alpine wonderland of 8,500 foot peaks, nicknamed "the Lost Sierra" and dotted with turquoise lakes, is decidedly untrammeled. Much of the area lies within the federally protected Lakes Basin Recreation Area, an under the radar gem dotted with 50 plus glacially carved lakes. For sweeping vistas of the lakes and surprisingly rugged peaks, follow 15 mile long Gold Lake Highway, which meets State Highway 89 about an hour north of Truckee.

Gold Lake, the biggest of the lakes, has a public boat launch and rental boats. Swim, fish, or water-ski in the morning, then sail or windsurf when the afternoon breezes pick up. At sunset, relax with cocktails at Sardine Lake Resort. Cabins and lodges line the shores of several lakes; alas, they’re usually booked months in advance by families who have been coming for generations. For a luxe option, check out Nakoma Golf Resort, about a half hour north, near Clio. Got your tent? Choose from a dozen drive-in campgrounds, including perfect-for-family sites at Sardine Lake, Salmon Creek, and Lakes Basin campgrounds.

Once you resolve your creature comforts, let your rugged side roam free. Kids love to romp along the easy trails to Upper Sardine Lake or Frazier Falls, while more intrepid hikers conquer the Lakes Basin’s obligatory challenge: the 178 steps to the Sierra Buttes Fire Lookout. It’s a roughly five mile round-trip hike to the tower’s base, then test your vertigo tolerance as you climb, climb, climb to its deck. If the ascent didn’t make you dizzy, the 360 degree view will. The panorama includes 10,457 foot (often snow-capped) Lassen Peak and the turquoise Sardine Lakes, sparkling 2,000 feet below.

Santa Rosa Island

California’s second largest isle, Santa Rosa Island measures a whopping 84 square miles—if you’re looking for isolation and adventure, this is the place. It’s a 3-hour boat ride each way from Ventura, so day trips aren’t practical.

"If you’re looking for isolation and adventure, this is the place."

Your best bet for exploring this expansive wilderness is to pitch a tent and stay at least one night at Water Canyon Camp, located near a 3-mile-long beach, and conveniently outfitted with showers, flush toilets, and wind shelters (a noted necessity in a place where strong winds are commonplace). So snug down the tent stakes before you head off to explore.

One must-do hike is Lobo Canyon, with its native flora, eroded sandstone formations, and embedded pygmy mammoth fossils. Pygmy mammoth? It sounds like an oxymoron, but a miniaturized 5-foot-/1.5-meter-high mammoth once roamed here. Other ambles lead to sandy beaches and a rare stand of Torrey pines (this island and San Diego are the only two spots where these wind-sculpted conifers grow).

Getting to Santa Rosa Island requires a 3-hour boat ride, or Channel Islands Aviation flies here in a mere 25-minute flight. It’s pricey, but if you’re prone to seasickness, it could be a worthy investment.

The Racetrack

In northern Death Valley lies a wind-blown playa called the Racetrack, where rocks are on the move. Stones, some as big as basketballs, travel in straight lines, curves, and even circles, leaving tracks imprinted in the mud. Then they stop suddenly, as if commanded by an unseen referee.

The sight of their tracks is enough to make you rub your eyes and wonder if you should see your optician. But even without the sliding rocks, the Racetrack’s ancient playa looks otherworldly, its blinding expanse of cracked mud stretching to the horizon. For the rocks to move, there must be weather: rain or sleet, followed by extreme winds racing across the playa. The wind pushes the rocks across the mud, scoring the surface with tracks up to 1,500 feet long that last for months, or until the next hard rain. Human footprints can do the same, so visitors are asked to view and photograph the playa from its edge.

A trip to the Racetrack requires most of the day if you’re starting from Furnace Creek. Follow State 190 north to Scotty’s Castle Road, then follow that for 32 miles. Stay left at the fork to take Ubehebe Crater Road for six miles, then the pavement ends. Only high clearance vehicles should continue, as you’ll bump along on dirt for another 26 miles.