For the latest on COVID-19 (Coronavirus) click here

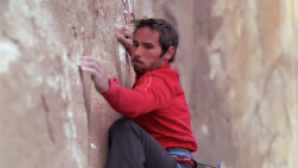

Kevin Jorgeson Reflects on the Dawn Wall Ascent

Kevin Jorgeson spent 19 days last December and January quite literally focused on scaling a massive wall. He was also trying to avoid the inevitable fact that his life was about to change dramatically.

The climber from the Northern California town of Santa Rosa and his friend, Tommy Caldwell, were attempting to become the first people to free-climb the Dawn Wall, the imposing 3,000-foot rock face on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. As they made their way up the mountain—climbing in the evening or at night when the temperatures dropped and the rock cooled—the world watched with growing fascination.

“I had friends texting me, ‘Dude you’re on TV. It’s crazy, like every night.’ I’m like, ‘Oh my God.’”

On the wall, Jorgeson could sense the increasing interest. “We couldn’t avoid it. We tried a little bit, but when your Instagram audience goes up by 10 times in a couple days, you know something is happening,” he says. “I had friends texting me, ‘Dude you’re on TV. It’s crazy, like every night.’ I’m like, ‘Oh my God.’”

But at the same time he knew that he needed to focus on the task at hand: accomplishing a climb no one had done before, one that many thought was impossible. The Dawn Wall consists of 32 pitches—one pitch is the length of a climbing rope—and Caldwell, the more experienced of the pair, got through the toughest part with relative ease. Jorgeson, however, couldn’t climb pitch 15, an incredibly technical section that required grabbing two of the smallest, sharpest holds on the rock face. Ten times he tried, and 10 times he failed, each time returning to their hanging base camp to let the skin on his fingertips heal.

Then, on January 9, Jorgeson made another attempt. He was fuelled by a breakfast of a whole wheat bagel with cream cheese, cucumber, red bell pepper, and salami, and encouraged by a slight tweak in his technique he discovered after a documentary crew sent him a compilation of his previous failed attempts. With Caldwell pushing him onward and the world watching, the then-30-year-old finally mastered pitch 15.

“As I stood at the anchors of pitch 15, I remember the sound of the wind and my breathing,” he says. “It took a few seconds before I had any kind of self-awareness. When it came, I was overwhelmed with relief, energy, and satisfaction. As our hoots and hollers washed down the wall toward the meadow, we could hear the cheers coming from the crowds looking up at us.”

"I’ve never done a press conference before. I’ve never been on Good Morning America. What the hell?”

From there, the climbing wasn’t over, but the hard part was done. Five days later, Jorgeson and Caldwell stepped onto the crown of El Capitan, their task accomplished, their lives forever changed. “When we got to the top, there was no hiding,” he says. “You cannot imagine two more different worlds: being on a wall for three weeks, and then coming down to what we came down to. I’ve never done a press conference before. I’ve never been on Good Morning America. What the hell?”

Jorgeson went on GMA. He served as the grand marshall at a NASCAR race. He met Steve Young backstage at a speaking event, and was shocked and flattered to find out the Hall of Fame quarterback followed the ascent. He threw out the first pitch at a San Francisco Giants game. (“Probably the scariest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he says.) He slowly got to a point where he wasn’t surprised when random people mentioned the climb in conversation. He started to understand the impact, how much it fascinated the general population, and why it resonated.

Still, it was all a little surreal. “[Everybody else's] perception of us, and who we are and what we had done, was different than our own self-perception of it,” Jorgeson says. “It’s like coming down and now red is blue, but you’re the only one who still thinks red is red.”

And, of course, life continues. He's prepping another potential ascent of El Capitan, a different, challenging line that's appropriately called New Dawn. While climbing the Dawn Wall – a project Jorgeson joined in 2009, after Caldwell scouted the line and had completed much of the preparation – the pair would point out features elsewhere that they believed they could climb, and Jorgeson thinks this might be his next challenge. "Now that the Dawn Wall is complete, I’m eager to experience the big wall first ascent process from start to finish.” He'll investigate further during this spring and the coming autumn, and many of the details like whether Caldwell joins any effort or if it's even climbable remain to be seen. "There's lots of uncertainty, it may or may not be possible and it's likely to be very difficult," he says.

“What unseen climbing is out there because you need a boat to get to it?”

He’s also excited about combining his first love, white water rafting, with his second, using boats to get to climbing spots that aren’t accessible via foot. The initial expedition is set for the Eel River in north western California. It’s a remote stretch of river that Jorgeson has done a few times with his father and brother but always through the eyes of a rafter rather than a climber. He can’t wait to see find out what he can discover. “What unseen climbing is out there because you need a boat to get to it?” Jorgeson wonders, always looking to the next adventure while revelling in the past.